Naruhito & Masako, Emperor & Empress of Japan, conducted a three day visit to the United Kingdom this week. It was the third state visit to Britain during the present reign, and the first monarchical one since that by the King & Queen of the Netherlands in 2018.

The visit consisted of the expected activities – a state banquet at Buckingham Palace, then another banquet at the London Guildhall, as well as military parades and presentations.

According to the Court Circular for 25 June, the palace guest list included “Mr. Christopher Broad (Founder of YouTube channel, Abroad in Japan)”. This is thought to be the first time that a prominent YouTuber has been invited to a state event specifically in that capacity.

As is customary during state visits, the monarchs exchanged appointments to their respective orders of chivalry: Charles received the Collar of the Supreme Order of the Chrysanthemum while Naruhito became a Stranger Knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. It is a shame that his visit was not a few days earlier, or he could have marched in the procession.

Sodacan’s representation of the Japanese Garter arms.

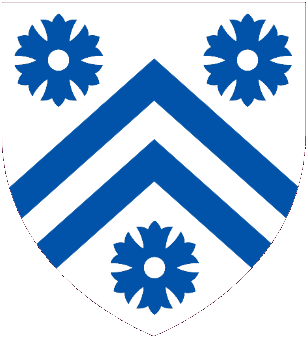

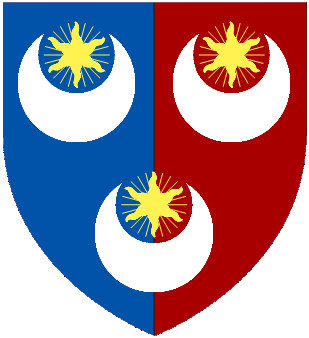

Naruhito ascended the imperial throne in 2019 when his father Akihito abdicated. Japan now joins Spain and the Netherlands in having two Garter stalls simultaneously. What makes the Japanese representation different to the Spanish and Dutch is the different style of heraldry. The Japanese Imperial Seal is a mon representing a stylised chrysanthemum flower. Mon are normally standalone objects without a background – more visually similar to a Western crest or livery badge than a shield of arms. To make the symbol compatible with European heraldic customs for use in St George’s Chapel it is typically presented as the lone charge on a red background for the shield and banner, then again without a background as the crest atop the helm. The Emperor paid a private visit to Windsor Castle to view his predecessors’ stall plates there and to lay a floral wreath on Elizabeth II’s tomb.

The state banquet also marked the first appearance of the Royal Family Order of Charles III. Dating back to the reign of George IV, the royal family orders are an informal and highly personal decoration restricted to senior royal women. Each consists of a silk ribbon from which hangs a jeweled miniature portrait of the sovereign. The orders do not always have formal classes but their badges tend to come in different sizes which correlate to the seniority of the recipient. The colour of the ribbon varies: Charles III follows George V in using pale blue, whereas Victoria used white, Edward VII blue and red lined with gold, George VI pink and Elizabeth II yellow. The Queen was seen wearing the new Carolean order immediately above the Elizabethan one she received as Duchess of Cornwall in 2007, and there is a clear difference in size. The Duchess of Edinburgh also wore Elizabeth’s order to the banquet.

This state visit was a little unusual in that it happened during a general election campaign. Some changes had to be made to the itinerary to cut out the more obviously political elements: Unlike previous visiting sovereigns, the Emperor did not make an address to Parliament (since their isn’t one) and while the cabinet and opposition leaders attended the state banquet they did not have individual meetings with him. Notably Sir Keir Starmer and Sir Edward Davey were not wearing their respective knightly insignia.

The four months of 2024 so far have been at the low end, with only thirteen illustrations in the year so far – and April in particular having just one – that being the nineteenth-century judge Arthur, Lord Hobhouse.

The four months of 2024 so far have been at the low end, with only thirteen illustrations in the year so far – and April in particular having just one – that being the nineteenth-century judge Arthur, Lord Hobhouse.