Another lecture from the Church Monuments Society, given by Dr William Roulston.

Category Archives: Interest Pieces

The Archives Arrive

The BBC Archive YouTube channel claims to have existed since 2018, but their videos only go back three months. I discovered them just yesterday. My favourite thus far is an interview with J. R. R. Tolkien explaining the writing of The Lord of the Rings. Also featured is the Shildon steam celebration of 1975, which includes an interview with Wilbert Awdry (strangely called “William” in the voiceover), and at least two short documentaries about the making of Classic Doctor Who.

It’s too early yet to know just how many videos this channel will post. If it’s anything like British Pathé I will be greatly impressed.

Ever to Succeed

News has broken that two days ago Her Royal Highness Princess Beatrice, Mrs Edoardo Mapelli Mozzi, gave birth for the first time. Her yet-unnamed daughter is eleventh in line to the throne. I wished to edit the relevant Wikipedia article accordingly, but that proved difficult as the list had multiple levels of indentation to reflect the generations and all the numbers had to be changed manually.

There is a challenge in deciding just how many names to include on the page. The legitimate non-Papist descendants of George I’s mother number well into the thousands nowadays and the vast majority of them are non-notable. The editors have here decided to limit the display to the descendants of the sons of George V. In practice this just means Bertie, Harry and Georgie, since David and John both died without issue. Even that restricted selection comprises sixty-three living people, of whom thirty-two have no pages of their own.

The clumsiness of editing this list brought up an idea I had some years ago for giving each member of the diaspora a numerical code to indicate their position within the succession. The electress herself, being the origin of the succession, would be 0. Her eldest son Georg Ludwig would be 1, her next son Frederick Augustus 2, Maximilian William 3 and so on. For each generation a digit is added, so Georg’s offspring George Augustus and Sophia Dorothea would be 1.1 and 1.2, while George Augustus’s children would be 1.11, 1.12, 1.13 and so forth. Under this system Princess Alexandrina Victoria of Kent & Strathearn would be 1.11141 while Princess Elizabeth Alexandra Mary of York would be 1.111411221. Prince Philip of Greece & Denmark would, I think, be 1.111416331. The beauty of this system is that the crown always goes to the living person with the lowest number, rather than each new birth or death close to the throne forcing everyone downstream to be renumbered.

There are downsides, of course. First, there is always the danger of one day discovering a missing sibling who died young and was forgotten to history. Second, until the commencement of the Perth Agreement the crown followed male-preference primogeniture, so any girl’s code was liable to change upon the arrival of a brother. Third, if any person in the line has more than nine legitimate children then the numerals would be inadequate (as in George III’s case, though perhaps there one could only number his nine sons and omit his six daughters, none of whom had surviving children of her own), and an alphabetical system might be needed instead – Elizabeth II would be AAAADAABBA and the late Prince Philip AAAADAFCCA.

On a related note, I have been keeping tabs on Judiciary UK for some months looking at new judgements as they come out. My main interest was Bell v Tavistock, but the day before that was resolved my eye was caught by the decision of Sir Andrew McFarlane (President of the Family Division) not to publish the Duke of Edinburgh’s will. Sir Andrew spoke at length about official etiquette regarding the royal family, and shed some light on that term’s definition. For Wikipedians, academics, press and others, there has always been a little confusion as to when membership of the family ends**. Is it the top X in line to the throne? Everyone descended from the current monarch? All descendants in the male line from George V? From Victoria? Everyone styled Royal Highness? Everyone on the balcony at Trooping the Colour? Then there are the gradations – often the headlines talk of “minor royals”, usually meaning the Dukes of Gloucester and Kent but sometimes including the Prince of Wales’s siblings and niblings, while mentions of “senior royals” are even more nebulous. One reason for this difficulty is that there are really three separate types of rank within group – precedence is determined by one’s relationship to the incumbent monarch, style and title by generations’ removal from any monarch and succession by primogeniture of descent from Sophia. McFarlane, in his judgement, may have given some more substance on which to build at least the latter’s definition.

From paragraph 15: This Court has been informed that in recent times the definition of the members of the Royal Family whose executors might,as a matter of course,apply to have the will sealed up has been limited to the children of the Sovereign or a former Sovereign, the Consort of the Sovereign or former Sovereign, and a member of the Royal Family who at the time of death was first or second in line of succession to the throne or the child of such a person. In addition, the wills of other, less senior, members of the Royal Family may have been sealed for specific reasons, or, as the list of names suggests, a wider definition of “Royal Family” may have been applied in this context in earlier times.

From paragraph 23: The confidential note that was disclosed and is attached to Charles J’s judgment contains an interesting account of the development of the practice of sealing Royal wills during the last century. That note provided that, in particular,the practice of applying to the Family Division applied, as a matter of course,to ‘senior members of the Royal Family’ who were defined as:

•The Consort of a Sovereign or former Sovereign;

•The child of a Sovereign or former Sovereign;and

•A member of the Royal Family who, at the time of His/or Her death, is first or second in line of succession to the throne or the child of such a person.

This means that, for judges’ purposes “senior royal” essentially means monarchs themselves, their consorts and their children (not necessarily children-in-law), as well as the first two in line to the throne and their children. Monarchs’ children are easy enough to spot from the rest, with the definitive article in their princely styles and their coronets of crosses interspersed with fleur-de-lys, but the latter category could be unstable – Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret of York would have been senior by this definition during their grandfather’s reign but would have lost that status had Edward VIII sired children of his own.

Applying it to the current situation, then, we can see that the seniors of the present royal family are:

- HM The Queen

- HRH The Prince Charles, Prince of Wales

- HRH The Prince Andrew, Duke of York

- HRH The Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex

- HRH The Princess Anne, Princess Royal

- HRH Prince William, Duke of Cambridge

- HRH Prince Henry, Duke of Sussex

- HRH Prince George of Cambridge

- HRH Princess Charlotte of Cambridge

- HRH Prince Louis of Cambridge

There is one part of the judgement with which I take issue – paragraph 13 says It is understood that the first member of the Royal Family whose will was sealed on the direction of the President of the Probate, Admiralty and Divorce Division was His Serene Highness Prince Francis of Teck. Prince Francis was the younger brother of Princess Mary of Teck who, upon her marriage to King George V, became Queen Mary in 1910. Later that same year, at the age of 40 years, Prince Francis died. An application was made for the will to be sealed and not published. The application was granted. This is a little misleading, as Mary married Prince George, Duke of York in 1893 and became Queen on his accession in 1910. The judge’s text implies that she didn’t marry him until he was already King.

*Some in the press have claimed that as her father is an Italian count, the baby will be a countess, but the title is not recognised by the Italian republic or by the United Kingdom. Most likely she will be Miss [[Firstname]] Mapelli Mozzi.

**Of course, any family can present this difficulty as few are consciously defined by any formal rules.

UPDATE (1st October)

Princess Beatrice’s baby is named Sienna Elizabeth Mapelli Mozzi.

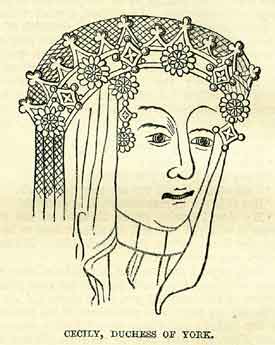

Cecily Neville by Annie Garthwaite

The latest installment in my EventBrite saga is today’s presentation to the Gloucester Branch of the Richard III Society by Annie Garthwaite, who has written a historical fiction piece about Cecily Neville (1415-1495), Duchess of York and mother of two kings.

The meeting properly began at 14:00 but the Zoom session was opened at 13:30. Cynthia Spencer, the host, said this was both to reduce the risk of interruption due to technical errors (or people arriving late) and to replicate in some way the socialisation between attendees that would occur at physical meetings. The first few minutes were thus filled with little more than awkward “Hello, hello?”s as early arrivals tested their sound systems. Garthwaite herself had to borrow an office with a fast broadband connection, her own being unreliable. There ensued a more general discussion as to the benefits and drawbacks of conducting all such meetings virtually. The ease of attendance from across a wider geographical area without a long commute was weighed against the subscription fee for the software. I opined that a virtual event’s main weakness was the impossibility of a buffet. Garthwaite recalled having virtual dinner parties – dinner for twelve people but only washing up for two! Inevitably there was talk about not being dressed below the waist.

After many more minutes of functional chatter, Keith Stenner (Chairman of the Gloucester Branch) announced that this was their first presentation of a fiction book. Garthwaite said that she had inherited her mother’s obsession with historical fiction and that her history teacher would pass books along to her. She was particularly enthralled by We Speak No Treason and developed an infatuation with Richard III – one obviously unrequited if for no other reason than the monarch having died five centuries prior.

Likeness by unknown artist circa 1540.

Cecily, the speaker noted, was born in the year of Agincourt and died in the reign of Henry VII. She was the only main protagonist of the Wars of the Roses to personally live through the whole of the conflict period, and spent much of that time as the most powerful woman in England save the queens themselves.

Garthwaite read out an extract from her book, set in Rouen in 1531 with Cecily observing Joan of Arc’s execution.

Returning to her background, she mentioned that she had long been familiar with other important women from the period – Margaret of Anjou, Margaret Beaufort, Elizabeth Woodville – and blamed Shakespeare for Cecily’s comparative obscurity. In his plays the duchess appears old, pious and dull, with few lines and little agency. Our guest went into an explanation of her subject’s childhood and courtship, then (with some fumbling around the screen-share function) showed us a simplified* diagram of Richard of York’s ancestry to demonstrate how he came about his multiple peerages as well as his two claims to the throne. She noted that, despite Richard clearly receiving royal favour at various points, he was always under suspicion from the Lancastrians.

Cecily’s arms – Richard Duke of York impaling Ralph Earl of Westmorland.

Garthwaite said she believed Richard & Cecily to be a marriage of equals, both being highly intelligent and ambitious – Cecily was allowed to operate autonomously in her husband’s business, household and political negotiations. It was a worryingly long time before the marriage produced any children but eventually she sired eight sons and four daughters (most of whom she outlived).

Garthwaite views Cecily’s marriage as the apprenticeship to her true flourishing as a widow, noting that when her son Edward IV acceded to the throne he immediately rushed off to the Battle of Towton, leaving the duchess in charge of the royal household “effectively as regent”, with ecclesiastical and diplomatic correspondence describing her as the true leader of England.

Describing the production process, Garthwaite said she – a novelist not a historian by training – was determined to stick as closely to known facts as possible. Medieval noblewomen did not solely concern themselves with embroidery and maternity, but would be in charge of managing large and complicated household organisations. Cecily’s family conflict was examined – her marriage into the House of York pitted her against her own Beaufort cousins.

After an anecdote about Destiny’s Stone on the Hill of Tara, another extract was read – concerning the Duke & Duchess’s last day in Ireland. This ended the formal presentation. Stenner noted that the book ended in 1461 but Cecily lived to 1495, and asked if a sequel was coming. Garthwaite confirmed that there would.

Spencer then began reading out questions that had been submitted by other attendees. One was about the allegation that Edward IV was the son of Blaybourne the archer and not Richard of York. Garthwaite laughed “I knew this would come up!” and said that the possibility of an affair was gold dust for historical novelists, but she decided that the theory was too tenuous.

Another was how a writer decides which historical events to include and which to omit, given Cecily’s very long life. Garthwaite said she learned to find the junctures which enable you to tell the overall story most clearly. She also said that “Your editor always has different opinions on it than you do.”

Spencer herself then asked about the legal status of decisions made by a woman in that era, and how her household was managed during confinement. Garthwaite replied that a lady of Cecily’s rank effectively had her own household distinct from her husband’s. After her husband’s death and her son’s accession she procured for herself very substantial tracts of land. This demonstrated, in the writer’s view, that female emancipation was not strictly linear – women of Cecily’s time wielded significantly more power than their Victorian or even later counterparts.

I asked Garthwaite what she thought of Cecily’s portrayal by Caroline Goodall in The White Queen and The White Princess** – the only instance I knew of her being played on television besides adaptations of Shakespeare plays. She replied that she had not seen either series and never passed judgement on other writers, but credited Philippa Gregory with renewing public interest in that era of history. Spencer chimed in that Cecily came across as a powerful person and that “It was a weird series but there were a few outstanding performances and I thought she was very good.”. Garthwaite said that while writing her own book she could not read anyone else’s historical fiction for fear of getting their thoughts mixed up with her own. This reminded me of Daisy Goodwin, writer of ITV’s Victoria, saying she would not watch The Crown to keep her own work independent and avoid plagiarism allegations.

The congregation then began to disperse but the session was kept open for a few more minutes so that members could scribble down contact details. I plugged my blog verbally for the first time, though I wish I had got in a moment earlier as by then there were only six out of thirty-one other people still logged in.

I have read and heard about the Richard III Society before but this was my first time directly interacting with its members. I hope there may be more.

*Inevitably, for a fully-detailed family tree for the Plantagenets, Beauforts, Nevilles and Mortimers would require multiple dimensions and still look tangled.

**Notably she was the only character not to be recast, perhaps because she was already an old woman when the first series started and so did not need to be aged up.

Public Domain Day 2017

In most of Europe, a work that is published within the creator’s lifetime remains under copyright for seventy years after their death. As 2016 ends, the works of people who died in 1946 become freely available to all. Such people include…

Helen Bannerman

Helen was born in Edinburgh, but after marrying an officer from the Indian Medical Service she moved to Madras for thirty years. She wrote several children’s books about the Indian people, most famously The Story of Little Black Sambo, in which a small child is chased around a tree by tigers. Bannerman was also the grandmother of Professor Sir Tom Kibble.

The Lord Keynes

Perhaps history’s most famous economist, John Maynard Keynes is the founder of the Keynesian school of economic thought which held that the state should intervene to buffer against depressions and recessions. He has a long list of publications over the course of thirty-six years, but his most notable is A Treatise on Money, where he said that a recession would occur where saving exceeded investment, and that a nation’s wealth should be measured by national income rather than possession of gold.

Paul Nash

Primarily an artist rather than an author, Nash was posted to the Western Front with the Hampshire Regiment where he made sketches of life in the trenches. When sent back to London with a broken rib, he completed a series of twenty images which went on exhibition twice. He was later commissioned as an official war artist. In his next outing to the front he made “fifty drawings of muddy places” which eventually formed another collection. In World War Two he was made an artist for the Royal Air Force where he produced paintings of aeroplanes and the Battle of Britain.

Herbert George Wells

Dubbed by some as the father of science fiction, Wells’s bibliography spans more than fifty years. As well as the obvious classics – The Time Machine, The Island of Doctor Moreau, The Invisible Man and The War of the Worlds – he also did non-fiction work such as Text-Book of Biology and a great many political publications such as War and the Future, The Way the World is Going and In Search of Hot Water and instruction books such as Little Wars which set out the rules for toy soldiers.

Further Reading: