Today I was a virtual attendee at the annual Mick Aston lecture by Dr Julian Richards. No write-up is needed this time because Cotswold Archaeology put the whole recording online.

Today I was a virtual attendee at the annual Mick Aston lecture by Dr Julian Richards. No write-up is needed this time because Cotswold Archaeology put the whole recording online.

For my first virtual lecture of 2025 I joined Leeds City Walking Tours, though obviously on this occasion I walked very little.

The presentation was by author and geographer Dr Rachael Unsworth, and it focused on the Art Deco architectural style of the interbellum period.

Art Deco was dubbed some some as the most glamorous style of the 20th century. It stood in stark contrast to the misery and gloom of the First World War. It had its antecendents in both the Beaux Arts and Bauhaus movements – the latter, Unsworth notes, has proven extremely influential on other artistic and architectural movements ever since despite not being very long-lived in its own right.

The Art Deco movement is traditionally traced back to the 1925 Paris Exposition, though the actual term “Art Deco” is a retronym not properly established until the 1960s. It overlapped with Modernism and was notable for sticking to some of the established rules of the preceding Classical period (especially regarding the overall shape of a building) while radically changing its ideas about materials and ornamentation. The decorative flourishes of this fashion focused on bold geometric shapes and the Greek Key symbol (of which Unsworth pointed out a few examples). It also saw the widespread adoption of Portland Stone, steel frames, reinforced concrete, “Crittal windows”, chrome fittings, vitrolite and fluorescent lights.

Dr Unsworth listed some of the “architectural lynchpins” of Art Deco – Charles Reilly, Robert Atkinson, Thomas S. Tait, Howard Morley Robinson – then some rapid-fire examples of the Art Deco buildings themselves. As you would expect from the name of her organisation, these were mostly focused on Leeds.

Particular attention was given to the university, where she brought up the anecdote of the Parkinson Building which was faced with Portland Stone at the front but ordinary brick at the lesser-seen back, because the latter was 4% cheaper. There were also some examples closer to (my) home, such as the Dorothy Perkins building in central Hull.

Unsworth closed out by noting the paradox of Art Deco – it was used as a component of national identity in some countries but stood for internationalism in others. It also stood for peace and democracy at the same time as standing for the power of dictatorships. The League of Nations headquarters in Geneva had the same aesthetics as the Reich Chancellery in Berlin.

She had hinted at the start of the lecture that this topic had particular salience at the moment. I had no idea what she meant.

FURTHER READING

Art Deco style is popular again, a century after its heyday – Associated Press

It has been a while since I attended any virtual events by the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada. Today’s was rather different in style to the ones I remember during the COVID years.

The speaker was Ann Marie Rasmussen, Professor and Diefenbaker Memorial Chair in German Literary Studies at the University of Waterloo. Her lecture was divided into three parts.

Badges are small devices found mainly in north west Europe. They were easy and cheap to make, usually from pewter in moulds carved from stone. We have an example of a surviving stone mould in Mont-Saint-Michel showing the image of St Michael slaying the dragon. Pewter can show fine details well, but it has the weakness of tarnishing easily. Currently there are more than twenty-thousand medieval badges surviving in museums, and during the middle ages there were probably more than a million in existence. Badges were designed to be decoded. Pilgrim badges were one type, made and sold at holy sites showing religious imagery (e.g. one from Canterbury shows Thomas Becket, one from the Vatican shows crossed keys with a tiara). There survives an anonymous painting of Christ himself among the pilgrims, all of them wearing badges.

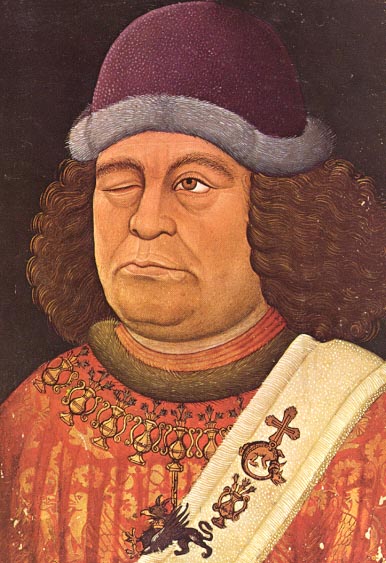

Almost all retainers and employees would have a badge to show the identity of the lord, household or organisation for which they worked. There are even examples of badges made of children’s toys. A 1432 portrait of the poet Oswald von Wolkenstein shows him wearing a badge of a dragon and griffin.

The separation of the spiritual and temporal realms is a modern idea. The types of badges often crossed over. Not all imagery was reverential – there are some humourous ones designed to resemble unsightly body parts, and there are records from medieval times of people complaining about indecent badges being worn and distributed around festival times.

EXTERNAL LINKS

UPDATE (June 13th)

The Society has uploaded the lecture to its YouTube channel, so I am spared from writing out a long description of its contents.

The Oxford University Heraldry Society’s May lecture was given by Vicky Fletcher. It was a study of pseudo-heraldic shield motifs in historic church graffiti and medieval personal seals. She began by confessing that she was not a heraldic expert, and so “heraldic” was here used in a broader than usual sense.

The idea of chivalric knighthood was significant in the late middle ages. Heraldry was a free-for-all until Richard III gave a charter to the College of Arms in 1484. Large amounts of land became available during the reign of Edward III due to, among other factors, population disruption from plague and famine. Labourers could demand higher wages and much arable land was converted to pastoral. New landowners used heraldry to bolster their social status. This was the age of the burgeoning “middling sort”.

Her in-depth study was of All Saints Church in Worlington, Suffolk. The parish church was the centre of medieval life, although the new rich were also prone to establishing private chapels. All Saints Church would be one of the first buildings encountered by people who arrived from the river. Fletcher had looked in depth at the many motifs carved into the church’s walls but decided to confine herself to those which were shield-shaped. There were an estimated 390 inscriptions were found in the church, of which around 10% were heraldic in nature.

Heraldic graffiti was mainly clustered around four of six piers in the south arcade. Motifs do not cut across each other and defacement is rare, though a lot of it would have been whitewashed during the Reformation and then clumsily scraped off by the Victorians. The most common motifs were the bend, the chevron and the quarter (which in Fletcher’s terms included crosses and saltires).

There are many prominent examples of the arms of Jerusalem, probably used by returning pilgrims. Peasant rebels in Richard II’s time used the arms of St George. Heraldic symbols were widely used by merchants. There were also “personal seals” used by individuals in a private capacity. Peasants who rose in status might want to disguise their low ancestry to escape the notice of their former masters (and thus avoid having to pay tax to them).

A link to the full paper can be found here.

The Oxford University Heraldry Society often plays host to reasonably esteemed academics in their field, but incumbent officers of arms themselves are a rare treat. This evening our guest speaker was Bruce Patterson, Saint-Laurent Herald of Arms in Ordinary and Deputy Chief Herald of Canada. He gave us an overview of the history of Canadian heraldry from the sixteenth century to the twenty-first.

Canada began as a colony within New France, and thus naturally used the French royal arms. In the 1760s sovereignty was taken over by the Kingdom of Great Britain and exercised by the Hudson Bay Company. In 1826 the Canada Company was created to recruit Brits to emigrate to the under-developed parts of the colony. Both of these corporations had grants of arms.

Grants of arms to Canadian citizens were mostly the responsibility of the College of Arms and the Lyon Court until 4th June 1988 when the Canadian Heraldic Authority was established as part of the Governor-General’s office. The government at the time deemed the existence of a home-owned heraldic authority to be an essential feature of a sovereign nation. The physical headquarters of the CHA are found at La Salle Academy complex, along with the rest of the Canadian honours system. The individual offices of arms within the authority are named after Canada’s rivers. The Chief Herald has a blue and black tabard, but the other heralds merely wear morning dress in contrast to their British counterparts (as illustrated by a photograph from the Diamond Jubilee pageant in 2012). The CHA has an arrangement with the CoA regarding the supply of drawings of older grants, and the former lacks the latter’s vast genealogical remit.

The Authority issues grants on letters patent and, like its parent institutions, allows recipients to choose the level of extravagance and ornamentation in their design. A distinctly Canadian feature is that the blazon is written in both French and English, with grantees able to choose which language takes precedence. Other distinctive Canadian features are that male and female armigers use identical arrangements of elements and that cadency is determined on a personal basis rather than according to any standardised convention. Canadian grants often combine symbols familiar in European and Inuit traditions – most prominently in the arms of Mary Simon.

Patterson rounded off with some illustrations of the royal achievement of Canada itself, as well as the sovereign’s banner of arms and the new variant of the Tudor crown.

The lecture aimed for breadth rather than depth (as this blog post likely reflects), and served better as an introduction for beginners than a deep dive for the devout. If this proves to be the teaser for a long-running series I would be overjoyed, especially as I have not found many session of the Royal Canadian Heraldry Society advertised on Eventbrite for quite some time.

Thomas’s daughter Margaret, painted in 1562, with the beast in the background.

After a long-ish break – the January lecture failing due to technical glitches – I returned to the Oxford University Heraldry Society for a lecture about the Tudor era nobleman Thomas Audley, 1st Baron Audley of Walden, and the mysterious animal that features as his heraldic supporter.

At the end of the lecture I asked a question that had been intriguing me for a while – why, in the early Tudor period, was there such an explosion of historically-prominent senior officials with the first name Thomas?

Phillips gave the answer that, prior to the reformation, Thomas Becket was one of England’s most venerated saints and so of course a high proportion named their sons after him. That just left me with the new question of why there weren’t so many Thomases in high office between Henry II and Henry VII’s reigns, but I didn’t get time to ask that one.

On an unrelated note, today marks the tenth anniversary of my registration as a Wikipedia editor. In terms of edit count rankings, I have climbed to number 5452. There was no grand celebration – not even an automated reminder – but I did discover a Ten Year Society to join, albeit one with little activity thus far.

Today’s virtual event was put on by the Getty Museum.

This was a virtual discussion by “Glasgow 2024 Presents…” concerning the legendarium, its legacy and its adaptations.

This evening I attended a virtual lecture at Arts University Bournemouth. The presenter was David Lund and the subject was the history of architectural model-making, particularly that of John Brown Thorp.

Modelling is an invisible profession to most people as the model-makers are largely executing the ideas of architects, who thus take all the credit for the design. British model-making kicked off in the late sixteenth century with the arrival of trends from Italy. The earliest record is of a 1567 model of Longleat House, made for Sir John Finn. Sir Christopher Wren would go on to commission architectural miniatures on a regular basis.

Originally timber was favoured for model-building, but card proved to be more adaptable. Thorp is considered the grandfather of architectural model-making. He had his headquarters near to the Inns of Court, and his extremely-detailed scale models were used in court cases. By 1940 his firm was employing forty other modellers. The emergence of modelling as a dedicated profession allowed an increase in the size and standards of their creations.

Modelling boomed in the 1950s and ’60s, with the material fashions of the models changing in line with those of the buildings themselves – card representing brick was replaced by perspex representing glass and steel. The economic slump of the 1970s caused a change in clientele, with modellers working for private developers instead of state architects. Nowadays it is common for models to be designed on computers and then 3D-printed, incorporating lighting and even animation.

In the Q&A session, Lund was asked about the phenomenon of public disappointment when a finished construction fails to live up to what the model promised. Lund conceded that models and artistic renderings often gave a sanitised, optimistic prediction of the built environment, replete with happy people and clean surfaces, whereas the reality (especially in modernist constructions) proved quite different. Developers and the public often unfairly blame the artists and modellers for this, even though they are only following what the developers tell them to do.

On an entirely unrelated note, late last night I discovered that Sir Lindsay Hoyle, Speaker of the House of Commons since 2019, has finally been granted a coat of arms. I was relieved to come across this news at all, yet also a little perplexed to realise that the news articles were from almost a month ago. I don’t know how I missed this, given that I have been obsessively looking out for this ever since his election. The not-so-grand reveal came at the unveiling of a new set of stained-glass windows in the Palace of Westminster, the other panels of which were decorated with the arms of British Overseas Territories.

None of the news articles I have uncovered so far gave the blazon for the new achievement, so my illustration for Wikimedia Commons is based on visual inspection of the artwork in the photograph. It indeed includes the red rose of Lancaster, “busy bee” and rugby references as Sir Lindsay hinted two years ago. The use of the parliamentary mace Or on a fess conjoined to a bordure Vert is almost certainly copied from the arms of Sir Harry Hylton-Foster, who became speaker sixty years before Hoyle did – though one has to hope that Hoyle does not end his tenure quite so abruptly. The window shows mantling Gules and Argent (rather than Vert to match the shield), so I have copied that. It is not clear exactly when the grant was made, nor whether the grant was to Sir Lindsay himself or to his noble father (the mace makes the latter seem unlikely).

The search for other new grants continues. Last month I got a pretty strong hint about the arms of Lady Amos, but those of Sir Tony Blair remain as elusive as ever.

Today’s virtual lecture was presented by Owen Ryles, Chief Executive of the Plymouth Athenaeum. It concerned the time that the Duke of Clarence (later King William IV) visited the naval yards at Plymouth.

The lecture began with a preamble establishing the titular character: William was his father’s third son, long expected to lead a relatively quiet life. Even his creation as Duke of Clarence & St Andrews was not guaranteed, being granted only because he threatened otherwise to stand as MP for Totnes. He was sent into the navy at age 13 to keep him away from the perceived negative influence of his elder brother George IV. In his active career he was the first British royal to set foot in the American colonies, took command of HMS Pegasus in 1786 and gave away Frances Nisbet in her wedding to Horatio Nelson in 1787. He was commissioned as an honorary admiral in 1798, and then appointed to the office of Lord High Admiral in 1827 during the brief ministry of George Canning. In his private life, he scandalised Georgian society by cohabiting with his mistress Dorothea Bland and siring ten illegitimate children with her. He gave her a stipend on the condition that she would not return to acting, and later took legal action against her when she did anyway. When his niece Princess Charlotte of Wales unexpectedly died in childbirth William moved up in the line of succession and was forced into a royal marriage, but his wife’s children all died young.

For the grand occasion the duke arrived on HMS Lightning to a deafening chorus from onlookers. He did not disembark until 7pm. He visited the original Admiralty House, later renamed Hamoaze House, and met the Superintendent of Works Jay Whitby. On 12th July he inspected the Plymouth Division of the Royal Marines and said that Plymouth was his favourite naval resort (it was also the first borough in which he had been made a freeman). On 13th he received a loyal address by the mayor and municipal corporation at the Royal Hotel. Among the military men with whom he dined was his own son, Colonel Frederick Fitzclarence.

Also during the visit he laid the top stone of the sea wall at the Royal William Victualling Yard and donated ten guineas to each of the workmen. He also witnessed a demonstration by William S. Harris of the application of fixed lightning conductors to ships.

William’s tenure as Lord High Admiral did not last long – the next year he was dismissed after taking HMS Britannia to sea for ten days without government permission. In 1830 he acceded to the throne, the eldest until Charles III last autumn. He was reluctant to have a coronation at all, eventually spending just £30k on it compared with his elder brother’s £420k. His reign was short, and he clung to life just long enough to see his niece Victoria come of age. He was regarded as the “least obnoxious Hanoverian”, which some might consider high praise.