At 4pm today (or 11am for them) I attended yet another virtual lecture put on by the Toronto Branch of the Royal Heraldry Society of Canada. The speaker was Bernard Juby and the topic was heraldic bookplates – meaning a decorative label pasted into the early pages of a book, illustrating the arms of the copy’s owner. Juby told us, and showed many examples, of heraldic artists in Canada and around the world who had been commissioned to make such pieces. He said that the convention began in late fifteenth-century Germany, and that until relatively recently books of all kinds were primarily owned by the elite social classes, most of whom would be armigers.

His presentation focused on breadth rather than depth, moving at considerable speed through the portfolios of over a hundred artists. The rushing by of so many luxuriously detailed and coloured artworks was quite dazzling. It was indicated that a recording of the presentation will shortly be available on the society’s YouTube channel, so I need not attempt to describe them all again.

Towards the end of this presentation, Jason Burgoin casually mentioned that later in the same day the British Columbia & Yukon branch of the society would be holding its annual general meeting. This began at 1pm BC time, which was 4pm in Toronto or 9pm in Yorkshire.*

The meeting was chaired by Steve Cowan. He welcomed the presence of Angélique Bernard, one of the branch’s patrons, and then announced that this would probably be the last Zoom meeting for a little while. He moved swiftly and efficiently through the agenda, including a handful of financial statements and appointments of various society officers (He noted that everybody else turned their cameras off at that point. “Very wise”.). The main concern was the content of The Blazon, the branch’s newsletter, and anticipation of upcoming commemorations (Commonwealth Day, Platinum Jubilee and the branch’s own fortieth anniversary). I was pleased to be able to witness this, as practice for the NERA’s AGM in May.

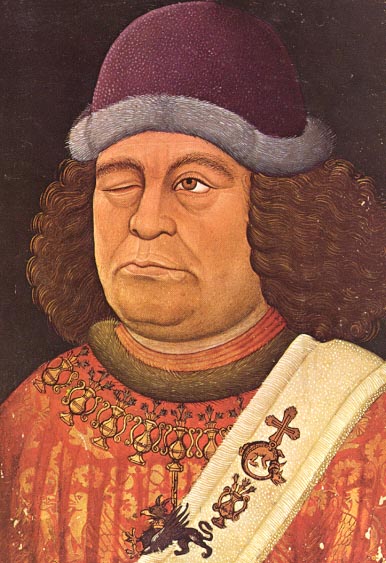

After an ten-minute adjournment, another presentation followed. This was by Charles Maier, former Athabaska Herald, and concerned the armorial history of Sir Winston Churchill. Maier said that while we often talk of him as one of the great men of history, his heraldry is great in itself. Winston was born a nephew of the Duke of Marlborough. He was proud of his lineage but also wanted to secure his own accomplishments. It is a lingering curiosity that he consistently refused to differentiate his own arms from those of his uncle.

The first Sir Winston Churchill was a cavalier soldier who was stripped of his lands and wealth under the republic. It was most likely during this time that the motto “Faithful Though Disinherited” was adopted. His branch of the family had borne arms Sable a lion rampant Argent over all a bend Gules, but in Charles II’s reign the bend was removed and replaced with a canton Argent thereon a cross Gules, presumably as an augmentation in reward for his services.

The first Sir Winston Churchill was a cavalier soldier who was stripped of his lands and wealth under the republic. It was most likely during this time that the motto “Faithful Though Disinherited” was adopted. His branch of the family had borne arms Sable a lion rampant Argent over all a bend Gules, but in Charles II’s reign the bend was removed and replaced with a canton Argent thereon a cross Gules, presumably as an augmentation in reward for his services.  The crest, a lion holding a red flag, also seems to date from this time. John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, was also made a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire in 1704 and Prince of Mindelheim in 1705. This allowed him to use the Imperial Eagle as a supporter behind the shield in addition to the wyverns on either side. A further augmentation (an inescutcheon Argent a cross Gules, surmounted by another inescutcheon Azure three fleur-de-lys Or) was granted in time for his funeral in 1722, and carried on flags in his procession. A special act of Parliament allowed Churchill’s English peerages to pass to his daughters, and through them into the Spencer family. The Spencer dukes gave their own quarterings priority over his until 1817 when they swapped them around and changed their name to Spencer-Churchill. They used a griffin and a wyvern as supporters. The modern day dukes continue to use the heraldic accoutrements of their principality, despite titles of the Holy Roman Empire never being allowed to pass through the female line, and also in spite of all German monarchies having been abolished in 1918. I found it a little strange that the Churchills continue to cling to a token given by the Germans for defeating the French, given that their name is now associated with saving the French from the Germans.

The crest, a lion holding a red flag, also seems to date from this time. John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough, was also made a Prince of the Holy Roman Empire in 1704 and Prince of Mindelheim in 1705. This allowed him to use the Imperial Eagle as a supporter behind the shield in addition to the wyverns on either side. A further augmentation (an inescutcheon Argent a cross Gules, surmounted by another inescutcheon Azure three fleur-de-lys Or) was granted in time for his funeral in 1722, and carried on flags in his procession. A special act of Parliament allowed Churchill’s English peerages to pass to his daughters, and through them into the Spencer family. The Spencer dukes gave their own quarterings priority over his until 1817 when they swapped them around and changed their name to Spencer-Churchill. They used a griffin and a wyvern as supporters. The modern day dukes continue to use the heraldic accoutrements of their principality, despite titles of the Holy Roman Empire never being allowed to pass through the female line, and also in spite of all German monarchies having been abolished in 1918. I found it a little strange that the Churchills continue to cling to a token given by the Germans for defeating the French, given that their name is now associated with saving the French from the Germans.

The later Winston was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1941, allowing him to use the arms of that office. He became a Knight of the Garter in 1953, requiring a banner and stallplate of his arms to be placed in St George’s Chapel. Churchill disliked his first banner and had another one made in “a more striking, modern style”. He also had two stall plates – the first was made by Harold Soper in 1954, but never affixed because the herald responsible was not satisfied with its artistic quality. The second was made in 1958 by George Friend. He received a state funeral in 1965. This was conducted by the Earl Marshal, who had Nelson and Wellington as his only precedents. Banners of Churchill’s own arms, and those of the Cinque Ports, were held by heralds in his procession. The funeral banner had a small blue crescent for difference, which Churchill had refused to use when alive. The coffin went from Victoria to Bladen by train, the namesake locomotive bearing a plaque of his arms on its boiler.

The later Winston was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1941, allowing him to use the arms of that office. He became a Knight of the Garter in 1953, requiring a banner and stallplate of his arms to be placed in St George’s Chapel. Churchill disliked his first banner and had another one made in “a more striking, modern style”. He also had two stall plates – the first was made by Harold Soper in 1954, but never affixed because the herald responsible was not satisfied with its artistic quality. The second was made in 1958 by George Friend. He received a state funeral in 1965. This was conducted by the Earl Marshal, who had Nelson and Wellington as his only precedents. Banners of Churchill’s own arms, and those of the Cinque Ports, were held by heralds in his procession. The funeral banner had a small blue crescent for difference, which Churchill had refused to use when alive. The coffin went from Victoria to Bladen by train, the namesake locomotive bearing a plaque of his arms on its boiler.

Maier pointed to some other examples of his heraldic legacy – HMS Churchill, HMCS Churchill, Churchill College Cambridge and the 1965 Churchill postal stamp, whose launch coincided with the introduction of the modern flag of Canada, ironically symbolic of the passing of the very age with which he was most associated. His arms were also borne, impaled, by his daughter Mary Soames, who became a Lady of the Garter in 2005. Of course, he also brought up Churchill’s time in Canada: The famous “roaring lion” portrait was taken by Yousuf Karsh in 1941, and Churchill’s expression is of anger at having his cigar taken away. William McKenzie-King, Prime Minister of Canada at the time, was desperate to be photographed with Churchill, though that picture is less well known. When Churchill was Secretary of State for the Colonies he argued with the Garter King of Arms about whether a warrant or a proclamation was needed for Canada’s new blazon.

Maier pointed to some other examples of his heraldic legacy – HMS Churchill, HMCS Churchill, Churchill College Cambridge and the 1965 Churchill postal stamp, whose launch coincided with the introduction of the modern flag of Canada, ironically symbolic of the passing of the very age with which he was most associated. His arms were also borne, impaled, by his daughter Mary Soames, who became a Lady of the Garter in 2005. Of course, he also brought up Churchill’s time in Canada: The famous “roaring lion” portrait was taken by Yousuf Karsh in 1941, and Churchill’s expression is of anger at having his cigar taken away. William McKenzie-King, Prime Minister of Canada at the time, was desperate to be photographed with Churchill, though that picture is less well known. When Churchill was Secretary of State for the Colonies he argued with the Garter King of Arms about whether a warrant or a proclamation was needed for Canada’s new blazon.

Patrick Crocco asked if there was any particular system for assigning Garter stalls. Maier said it was simply whichever stall had been recently vacated. He also mentioned that HM Treasury covers all expenses relating to the order’s insignia.

There followed even more post-presentation chat, including a lengthy discussion between Cowan and Burgoin about women’s naval bowler hats. Sean from New Zealand was again present with his baby (whose burblings could be heard). I said that I had spent much of the past two years baby-sitting, thus becoming familiar with the heraldic banners featured in Ben & Holly among other programs. I also mentioned that I had been reading The History of the English-Speaking Peoples aloud to my mother, and trying to master Churchill’s voice.

All in all, today’s three events took up a lot of virtual time, but was well worth it. More are coming soon.

FURTHER READING

*A considerable amount of the post-presentation chat concerned the confusion that arises due to holding virtual meetings across multiple time zones. To make matters worse, different countries do daylight savings at different times – in Canada it begins tomorrow, but in Britain not for another fortnight.

The later Winston was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1941, allowing him to use the arms of that office. He became a Knight of the Garter in 1953, requiring a banner and stallplate of his arms to be placed in St George’s Chapel. Churchill disliked his first banner and had another one made in “a more striking, modern style”. He also had two stall plates – the first was made by Harold Soper in 1954, but never affixed because the herald responsible was not satisfied with its artistic quality. The second was made in 1958 by George Friend. He received a state funeral in 1965. This was conducted by the Earl Marshal, who had Nelson and Wellington as his only precedents. Banners of Churchill’s own arms, and those of the Cinque Ports, were held by heralds in his procession. The funeral banner had a small blue crescent for difference, which Churchill had refused to use when alive. The coffin went from Victoria to Bladen by train, the

The later Winston was appointed Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1941, allowing him to use the arms of that office. He became a Knight of the Garter in 1953, requiring a banner and stallplate of his arms to be placed in St George’s Chapel. Churchill disliked his first banner and had another one made in “a more striking, modern style”. He also had two stall plates – the first was made by Harold Soper in 1954, but never affixed because the herald responsible was not satisfied with its artistic quality. The second was made in 1958 by George Friend. He received a state funeral in 1965. This was conducted by the Earl Marshal, who had Nelson and Wellington as his only precedents. Banners of Churchill’s own arms, and those of the Cinque Ports, were held by heralds in his procession. The funeral banner had a small blue crescent for difference, which Churchill had refused to use when alive. The coffin went from Victoria to Bladen by train, the  Maier pointed to some other examples of his heraldic legacy – HMS Churchill, HMCS Churchill,

Maier pointed to some other examples of his heraldic legacy – HMS Churchill, HMCS Churchill,