Red Dwarf is a science fiction comedy series about a man from the twenty-third century who gets put into stasis and wakes up three million years in the future. As such, one would not expect it to include much in the way of medieval heraldry. Indeed, mostly it doesn’t. However, much like Star Trek, the normally-futuristic series occasionally delves into history, and historical fantasy, by means of either time travel or simulation.

The episode “Stoke Me a Clipper” (1997) involves Lister spending a few minutes in a virtual reality game based vaguely on medieval England, featuring an unnamed King & Queen of Camelot. That term is normally associated with Arthurian legends, which are nominally set in the fifth and sixth centuries but have much of their imagery and iconography backported from much later eras. The scene we witness in this episode looks most likely to be set in the fifteenth century, though no detail is actually given about the overall plot nor the setting of the story and no claim is made to historical accuracy.

A great many heraldic banners are seen in this scene, which manage to almost, but not quite, resemble real historical blazons.

The most obvious of these is “The Good Knight” (John Thompson) who wears an off-model version of the royal arms of England: His tabard is quarterly Gules and Azure, the first quarter bearing two lions passant guardant in pale Or and the second quarter bearing three fleurs-de-lys two and one Or. Curiously the lower quarters were left blank, as were those on his back. Perhaps they were meant to be out of frame?

Screencap circa 6m17s

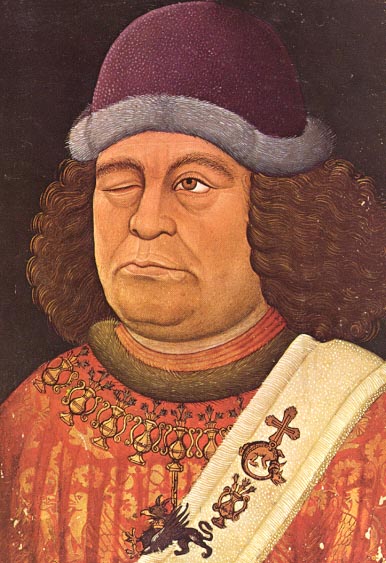

The King (Brian Cox) & Queen (Sarah Alexander) sit on a raised platform under a canopy on two ornate wooden thrones. Their gowns have no heraldic motifs but several are visible on the wall behind them. Above and between the thrones is a depiction of the coronet of a Marquess, the style of which probably dates to the seventeenth century. Lower down is a shield Argent a saltire between four fleurs-de-lys in cross although I am not certain of the latter’s tincture. At the top right of the screen is a shield with two piles reversed the point of each charged with a rose and in the top left is a shield parted per pale and charged with one large fleur-de-lis. Again the tinctures are uncertain. There are four rectangular images behind the thrones. The first looks to be Azure with at least two fleurs-de-lys Or (France again?) the second and third have a metal background with a fess chequy of a colour and a different metal (Clan Stuart?). The fourth cannot be seen as the consort’s throne obscures it completely from this angle.

Screencap circa 6m22s

Four banners are held aloft to the side of the throne area: That on the far right of the screen is divided per bend, the upper part being Azure four crosses fitchee Or and the lower being Gules fretty Argent. Closest to the platform is Azure seme-de-lis Or a double cross Argent over all a label of three points Argent. In between we have Quarterly 1st & 4th Vert a bend between two crosses flory Or 2nd & 3rd bendy of six Vert and Argent a label of three points Argent and Quarterly 1st & 4th Gules a bend between six crosses crosslet fitchee Argent 2nd & 3rd Gules three lions passant guardant in pale Or a label Argent. That last one bears more than a passing resemblance to the arms of the Howard Dukes of Norfolk.

Screencap circa 8m58s

We also see a trumpeter with a cloth shield hanging from his instrument. My best guess is Per fess Argent and Purpure in chief a cross throughout Gules impaling Gules three lions passant guardant reversed in pale Or. This is perhaps the least heraldic-looking of the bunch.

Screencap circa 6m7s

There are knights either side of the royal couple on the platform. That by the king’s right hand wears a tabard Ermine two piles Sable each charged with a lion rampant Or and that to the queen’s left Paly of four Azure and Argent on a bend Gules three birds displayed wings elevated Or. I cannot identify the birds from this distance but given heraldic trends they are most likely eagles, possibly falcons. Affixed to the roof of the stage is a shield which I would guess as Or a bend between two lozenges Sable each charged with a saltire of the field. The most obviously anachronistic element here (beside the decaying castle ruins, of course) is the tasselled embroidering at the front of the stage which shows a Georgian or Victorian depiction of the arms of the United Kingdom.

Screencap circa 8m16s

A man in the crowd (holding his helmet in front of his chest) wears a tabard which seems to be Per pale Sable and Or a label of three points Gules.

Screencap circa 8m37s

The trumpeter and a knight in the crowd both wear a tabard Gules two broken swords inverted Or on a pile reversed Azure fimbriated a broken sword of the second. Two children wear Chequy Or and Azure on a chief of the second three fleurs-de-lys of the first and yet another bystander wears something like Gules a crescent Argent between an orle of martlets Or.

Screencap circa 7m48s

A shot from the back of the crowd shows a knight with a helmet on wearing Vert on a pile Or a falcon’s head erased of the first and a man in a brown hat wearing Per pale Purpure and Argent a dragon passant counterchanged. Both animals are depicted as langued Gules.

Screenshot circa 9m14s

Lister’s own armorial bearings are difficult to make out – what we see on his outfit looks almost like the Russian double-headed eagle. There are a few other examples of heraldry in this scene but they are too faraway to read properly. Overall the resemblance of this scene is more to a Renaissance fair or a gathering of the Society for Creative Anachronism than to a typical period drama. Ugly faux-heraldry is avoided with almost all the arms shown being in keeping with the principles of good heraldic design, even if the matching up of arms to people is apparently entirely random.

I suppose Blackadder, particularly the first series, is the logical next stop for checking out heraldry in British television. Unfortunately that one doesn’t seem to be on iPlayer at the moment, nor can I find a convenient source of screencaps.

SOURCES