The King & Queen in Sydney (NSW Gov, CC BY 4.0). The King’s mouth is unfortunately hanging open in this shot, which combined with the opaque glasses makes for a bit of a Hubert Farnsworth look.

The King & Queen have just spent the past nine days on a tour of Australia and Samoa. Bizarrely, the Palace’s press release called this an “Autumn Tour” even though in the destination countries it was spring. The tour was originally supposed to have included New Zealand as well, but His Majesty’s cancer diagnosis earlier this year forced the itinerary to be severely reduced.

Charles wore three distinct metaphorical “hats” during the course of the tour: First as King of Australia conducting domestic business, second as King of Great Britain & Northern Ireland conducting a bilateral state visit, and third as Head of the Commonwealth presiding over the biennial Heads of Government Meeting.

Photographs of the sovereign couple at these events are unfortunately few and far between. Australian governments both federal and state lack official Flickr accounts with clear licensing indications as their British counterparts have, and the paltry few hosted on their websites are also of uncertain origin – at time of posting a handful have been accepted on Wikimedia Commons but these all look so suspiciously similar to those on Getty and Alamy that I wouldn’t be surprised if they ended up getting deleted shortly afterwards. There seem to be no free-licence photographs of the state visit to Samoa at all. Number 10 and the FCDO both have albums from the CHOGM, but only one picture of the lot actually shows Charles and none at all show Camilla.

I do not know the full details of the travel arrangements, but what I can gather is that Their Majesties and a small entourage took a commercial flight from Heathrow to Singapore, whence they were picked up by the Royal Australian Air Force and taken to Sydney Kingsford Smith Airport in New South Wales.

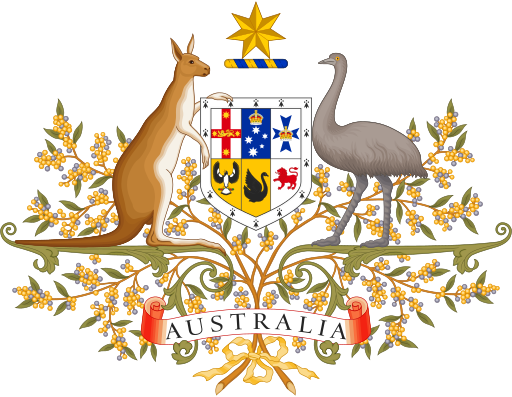

The tour marked the first in-the-fabric appearance of the Australian royal banner of arms (known officially as “The King’s Flag for Australia”), which was seen flying from the cockpit window and then later from several road and watercraft. The Australian banner follows Canada’s example by reverting to showing the national arms undifferenced, in contrast to the practice followed during Elizabeth II’s reign of defacing the banner with her own personal cypher. The King approved the present version on 30th August.

The current coat of arms of Australia was formalised in 1912. The shield is a composite in “quarterly of six” format, representing the six constituent states of the federation. The states of South Australia and Western Australia did not yet have full coats of arms at the time but all had heraldic badges (which are also shown on their respective civil flags) so these were used instead. The whole is surrounded by a bordure ermine.

The whole federal armorial achievement is normally depicted with the crest on a torse hovering some distance above the shield – omitting helm, mantling or coronet – but the Imperial Crown appears as a charge on the badges of Victoria and Queensland, notably at different sizes.

The whole federal armorial achievement is normally depicted with the crest on a torse hovering some distance above the shield – omitting helm, mantling or coronet – but the Imperial Crown appears as a charge on the badges of Victoria and Queensland, notably at different sizes.

As in Britain (though unlike Canada) the depiction of the crown in Australian royal symbols has changed from St Edward’s Crown to the Tudor Crown, though this has not yet entirely filtered through to all the state arms and flags themselves. I dimly remember – but can no longer find the proof – that the flag as approved on the government’s website in August still showed St Edward’s Crown, and that the graphic on Wikimedia Commons did likewise until photographs of the real flag caused an update.

The King at several points on the tour wore the sovereign’s badge of the Order of Australia along with a hefty line of other honours I will need time to identify. The Governor-General gave him honorary commissions at the top ranks of all three branches of the Australian armed forces. This is is a little perplexing from a legal perspective: One would have thought that the reigning monarch would hold these ranks substantively ex officio and would not need to be appointed to them by his own deputy.

The Queen is another story: For months now I have been looking out for signs of Camilla being granted the use of her own banner of arms – being the royal arms of the sovereign impaling those of her father Bruce Shand. This was finally seen to be the case during the Australian tour, flying from the bonnet of her car on a few occasions when she travelled without her husband. The videos did not show the flag long enough (and the stills tended to have it covered by the watermark) but from what little I can determine of the artistic subtleties of its design I reckon it is actually a printout of the vector file on the Commons. The car itself was a black Audi (I think a Q8) and the regular numberplates were obscured with plates bearing an image of the Tudor Crown. That image looks to have been taken from Wikimedia too, though I can’t find the exact image. The glaring problem here, of course, is that this banner shows Shand impaled by the British royal arms rather than the Australian, resulting in a mismatch with her husband. There is a burning irony that after all this time, the one occasion Camilla can be seen using a personalised banner of arms as Britain’s royal consort is the one occasion in which it was not appropriate to do so.

This unfortunately seems to be far for the course with royal tours – with the notable exception of Canada (probably because that country has its own heraldic authority), banners of royal arms in the other Commonwealth Realms seem to only be made for the reigning sovereign himself, with the rest of the royal family defaulting to their British blazons instead of coming up with a local variant. This may be marginally more convenient from a logistical and fiscal perspective, but it can be constitutionally misleading as it implies that they are representing a foreign state instead of that country’s own crown. If creating a personal one for each prince or princess is too onerous, it at least would be relatively easy to create a generic ermine-bordered version which they could all use when in the country. Admittedly that might not work in Australia where the sovereign’s own shield and banner have an ermine bordure already. For the royal wives, it might even make more sense to use banners of their paternal arms unimpaled so that they needn’t change based on location at all.

During the visit, His Majesty attended a service at St Thomas’s Anglican Church in North Sydney, made addresses to both the state Parliament of New South Wales and the national Parliament of Australia (sadly not from the throne in either case) and undertook a review of the fleet. God Save The King was played by a brass band while Charles inspected the troops and also by a solo amateur flautist during his walkabout but I can’t find any clip of it actually being sung at any point, in contrast to Advance Australia Fair which was sung by a children’s choir at Parliament House. That the monarch made no remark about his late friend Barry Humphries (a.k.a Dame Edna Everage) was also a little surprising.

When the royal party landed in Samoa they switched back to their British identities and the British royal banner was flown from the cockpit window alongside the Samoan flag, although the aeroplane itself was still very obviously branded as Australian.

While in Samoa Charles was invested with two honorific titles – Tui Taumeasina (King of Taumeasina) and Toa’iga o Tumua (Paramount Chief). The Queen was seen using a hand-fan with her royal cypher printed on it, which was given to her by Stewart Parvin in February. Both switched for much of the visit to bespoke white outfits in the local style.

Charles attended the CHOGM in his capacity as Head of the Commonwealth. Elizabeth II adopted a personal flag to represent herself in this capacity with no reference to any particular country. Her son so far appears not to have done so, which is a pity.

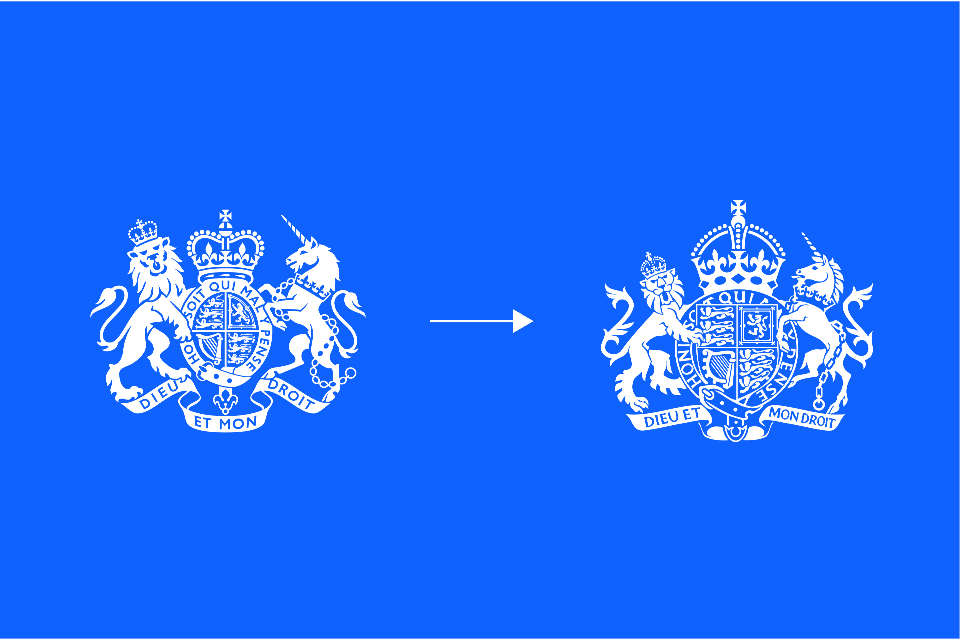

The official royal YouTube channel has uploaded some videos from these events. Not only are they continuing to use the outline of the British royal arms as the channel logo, they have also taken to including a new drawing of the arms in the thumbnails of individual videos. This, again, is a little problematic when the contents of the videos relate to other realms. I am left to wonder what recognisable symbol could be used here to avoid this problem. The livery badge of the House of Windsor might work, but even that technically has the British banner of arms included in it. The only solution that would truly work is, I suppose the CIIIR cypher on its own, without even a crown above it. Indeed, that could work for other family members’ flags and banners too.