Some notes on three recent topics which I did not deem worthy of full-length articles in their own right:

Andrew’s Arrest

Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor was yesterday arrested at his home on the Sandringham estate and taken for police questioning, being released later the same day. He is suspected of misconduct in public office.

The King put out a statement acknowledging the situation and essentially declaring that he would not interfere with the process of law. Of course, even if Charles is going to personally recuse himself, his position as incumbent sovereign means that his name will be frequently invoked during any legal proceedings, as any prosecution would formally be “The King against…” (written as “R -v-…”), the barristers arguing for both for and against Andrew would likely be King’s Counsel and if the former prince is incarcerated it would be in one of His Majesty’s Prisons, “at His Majesty’s Pleasure”. Also, of course, the royal arms will be used on a great many letterheads in the process.

Something similar happened with the Duke of Sussex’s lawsuits regarding his security provision: As a judicial review case it was formally “The King on the application of…” and the defendant was one His Majesty’s Principal Secretary’s of State. The case was, furthermore, heard in The King’s Bench Division. As reported in The Telegraph, this was

the infelicitous situation where the King’s son is suing the King’s ministers in the King’s courts. That is pulling the King in three directions.

The government is also apparently considering legislation to remove Andrew from the line of succession to the throne. Given that he is now eighth in line with the first seven all being at least twenty-three years younger than him, the effect of this will be more symbolic than practical. The need to coordinate any legal changes with the governments of the other Commonwealth Realms add further political friction. There have also been calls to formally remove his eligibility to serve as a Counsellor of State. His removal from the line of succession would do this automatically, but otherwise it could be done by a relatively simple Act of Parliament. This status only applies to Britain so the other Realms would not need to be consulted.

A principle that has been invoked many times during these events is that “No-one is above the law.” while it doesn’t help his brother, the phrase is not strictly true: The King himself is immune to arrest in all cases due to the principle of sovereign immunity which applies to varying degrees to lots of heads of state both monarchical and republican.

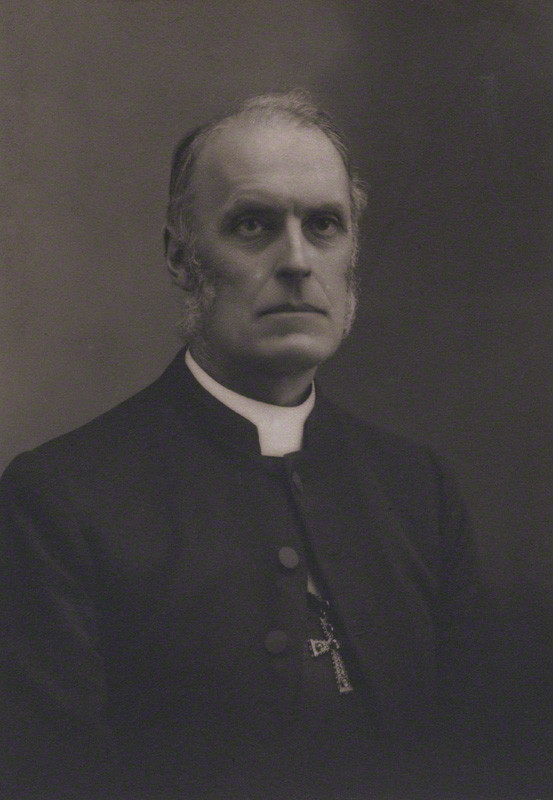

Bishopric Gets Bishop Rick

Yes, I am including this one solely for the pun. Richard “Rick” Simpson has been announced as the next Bishop of Durham. The diocesan office, one of the five ost senior bishops in the Church of England, has been vacant for nearly two years since the retirement of Paul Butler. In the interim the role has been delegated to Sarah Clark, Suffragan Bishop of Jarrow, who herself was recently chosen to become the next Diocesan Bishop of Ely. It should also be noted that Sarah Mullally, having had her election confirmed on 28th January, took her seat in the House of Lords two weeks ago, but will still not be installed at Canterbury Cathedral for another month.

Chagos Chaos

Donald Trump has flip-flopped yet again on the British agreement with Mauritius to cede sovereignty of the Chagos Islands. Recently a group of four Chagossians, led by Misley Mandarin, staged a landing on the islands themselves in protest at the attempted handover. The British government ordered their eviction but that has been temporarily blocked by a court order. There has been yet another “pause” of the passage of the relevant legislation through the House of Lords where scrutiny has been very strenuous and embarrassing for the executive.

More Publications, More Podcasts

Dominic Sandbrook, whom I count among the notable people with whom I’ve communicated, is mostly famous now as the co-host of The Rest is History, an enormously successful podcast. He has recently launched another podcast, The Book Club, which he co-hosts with Tabitha Syrett. Their first episode is on Wuthering Heights. Having not read it yet, I must try very hard to avoid repeating lines from the climax of Peep Show episode 39, clips of which I now very frustratingly cannot find. Twenty-five minutes in there is a discussion of the poems and songs in The Lord of the Rings, with Syrett saying she skips over them and Sandbrook saying they’re the best bit. When I read the trilogy aloud to my mother in 2020-21 I included all of them, turning to amateur channels such as Clamavi de Profundis for musical guidance. I have learned a great many of them by heart and practice them while walking the dog along the river bank.

Sandbrook’s idea for a podcast based on books is, of course, far from original. I have already blogged about two different book-related podcasts in the last few years and searching BBC Sounds for “book club” reveals quite a long list. The idea that literacy is essential to civilisation, and that the widely-recorded decline in reading over recent years represents a serious threat thereto, is gaining traction in intellectual circles. Times columnist James Marriott, whom I’ve had on my directory page since last summer, is fast emerging as the the leader of the movement. His own book, The New Dark Ages, is already gaining critical acclaim despite the fact that it isn’t due to be published for another few months.

Secretarial Succession

Dame Antonia Romeo has indeed been appointed Cabinet Secretary and Head of the Home Civil Service, a few days after the resignation of Sir Mark Wormald. Allegations against her have apparently failed to amount to anything.

Westminster Woes

Political power-couple Richard Marc Johnson and Lee David Evans, speaking on their own podcast (yes, yet another one), discuss the state of the Palace of Westminster (as I brought up last week). They also concur with the idea of putting Charles III in charge on the grounds that the royal family clearly has a much stronger track record with this than MPs, peers and civil servants do.