Today it was announced that The Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex and Forfar, was created Duke of Edinburgh, a title formerly held by his father. This had been speculated for years, but the intriguing part of the news is that the title is only for life – Edward’s son James will not inherit it. This is the first life peerage above the degree of baron for more than two hundred years, and the first given to a royal since medieval times.

For a newly-ascended king to denounce the principle of heredity seems unlikely. I think there is a more pragmatic reason for this – a desire to keep the title in circulation for the sons and brothers of future kings. The firm does not want to run out of place names (especially in Scotland) to use for dukedoms.

It has been tradition in Britain for the better part of a millennium that the younger sons of the monarch are granted dukedoms referring to prominent locations within the isles. Indeed, there is a lot of tradition in which particular place names are used, and even for which place in birth order.

On second thought, however, this shouldn’t be possible – if these honours are separately hereditary, and given to the offspring expected not to take the crown, then how do the same titles keep coming up time and time again. This paradox reveals an important detail about the royal dynasties of the past thousand years – their cadet branches normally don’t branch very far. It’s remarkably rare to find examples of a legitimate male line emanating from a younger son of a king that lasts for more than three generations. Most of the time either the junior line dies out (either only having daughters, or having no children at all), or the senior line fails so that the junior line ascends to the throne. To make matters worse, on the few occasions where a divergent line has managed to sustain itself, there has nearly always been some kind of intervention that prevented the title from doing so. What follows is by no means a complete history of the royal lineage, but a list of the most commonly-used royal dukedoms roughly in descending order of number of creations, with an explanation of what happened to them.

York

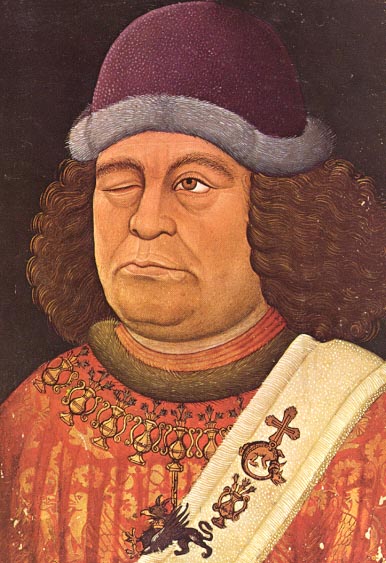

The first use of the northern city for a royal dukedom came in 1385, when Richard II bestowed the title on his uncle Edmund of Langley. This founded the House of York, which was to be one of the principal factions in the Wars of the Roses after Richard’s death. Edmund was succeeded by his son Edward of Norwich, who died at Agincourt, then his grandson Richard of York, who lead the opposition against the regime of Henry VI. Richard died before winning the throne, so the dukedom passed to his own son, who not long later succeeded as King Edward IV.

The title of Duke of York has since been conferred ten more times (thrice combined with Albany), nearly always for the monarch’s second son. Five dukes ascended to the throne, another four died without sons. Prince Andrew looks set to continue the latter tradition.

Sussex

Conferred twice as a dukedom – the first was for The Prince Augustus Frederick, sixth son of George III. He married twice without permission so his children were deemed illegitimate and the title died with him. The second was for Prince Henry of Wales in 2018. He currently has one legitimate son. It is too early to speculate about grandsons. An earldom of Sussex was also given by Queen Victoria for her son Arthur (see Connaught).

Gloucester

Created as a dukedom five times (and used as an informal style on two others), the most memorable recipient being Richard III. All died without an heir until Prince Henry, son of George V, whose son Richard (b. 1944) holds the title to this day. He has a line of succession two generations deep (though only one person wide) so barring any accidents for Xan Windsor we can expect the title to escape from the royal family for most of the rest of this century. The title “Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh” was created once and inherited once, the second duke dying childless in 1834.

Cambridge

Five creations and two more stylings. The first four dukes died as small children. Prince George (1706) and Prince William (2011) were both directly in line to the throne so their honours were doomed to merge. Prince Adolphus, son of George III, produced an heir but his children were born outside the Royal Marriages Act so they could not inherit. His daughter’s son, Prince Adolphus of Teck, was created Marquess of Cambridge in 1917 and passed it to his son George ten years later, but George only had a daughter and Frederick, his brother, died a bachelor.

Albany

First granted by Robert II to his third son (also Robert) in 1398, the title passed to his son Murdoch in 1420, but five years later Murdoch was attainted and his peerages removed. Conferred again by James II on his second son Alexander in 1458, it passed to his son John, but John died childless and brotherless in 1536. James V’s son Robert was styled as such in 1541, but he died at eight days old. Mary I conferred the dukedom on her husband Henry in 1565 and it was inherited by their son – later James VI, merging with the crown on his accession. James recreated the title for his second son Charles, but his first son died so Charles also became king. Charles II upon his restoration gave the title to his brother James, who succeeded him on the throne. Albany was also created three times as a joint peerage with York. The final creation was in 1881 for Victoria’s son Leopold, and inherited by his son Charles (also Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha) until he was stripped of it in 1919. The claimant today would be his great-grandson Prince Hubertus.

Cumberland

First created for Charles I’s nephew Prince Rupert of the Rhine, then William & Mary’s brother-in-law Prince George of Denmark, then George II’s son Prince William. All died without sons to succeed them. Prince Henry Frederick, George III’s brother, was made Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn in 1766, but he died childless as well. George later made his fifth son, Prince Ernest Augustus, Duke of Cumberland & Teviotdale. Ernest passed the dukedom (and the Hanoverian crown) to his son George in 1851, then grandson Ernest Augustus in 1878, but he was deprived of the title in 1919. The claimant today would be the first duke’s great-great-great grandson Prince Ernest Augustus (born 1954).

Kent

Ignoring non-royal creations, the title was conferred on George V’s youngest (surviving) son in 1934, and passed to his son in 1942. Currently the duke is fortieth in line to the throne, with two direct heirs and six spares of his own, so neither extinction nor merging is likely in the forseeable future. The double-dukedom “Kent & Strathearn” has been used once, for Queen Victoria’s father, but he died with no sons.

Clarence

Referring to the town of Clare in Suffolk, the first two creations were for the second sons of their respective kings, both dying without legitimate sons. The third creation was for George Plantagenet, brother of Edward IV. He was survived by a son, but the title was not passed on as he was attainted and executed for treason. The title fell out of favour until 1789 when George III made his third son (later William IV) Duke of Clarence & St Andrews. William had several children out of wedlock who used “Fitzclarence” as a surname. Queen Victoria ennobled her senior grandson Albert Victor as Duke of Clarence & Avondale in 1890, but two years later he died just before his planned wedding. An earldom of Clarence was already in existence, created nine years earlier for Victoria’s fourth son (see Albany).

Bedford

Granted twice to John of Lancaster, son of Henry IV, but he died childless. Conferred on John Nevill, intended son-in-law of Edward IV, in 1470, but he was later attainted for treason. Given in 1478 to George, said king’s third son, who died young. Given in 1485 to Jasper Tudor, uncle of Henry VII, who died childless. Given in 1694 to the non-royal William Russell, whose descendants carry it to this day.

Edinburgh

The first creation was by George I in 1726, for his senior grandson Frederick. Frederick predeceased his father, and the dukedom was held for nine years by his own eldest son, who then acceded as George III. Victoria gave it to her second son Alfred in 1866. He died in 1900, his only son having died the year before. The third and likely most significant creation was by George VI in 1947, for his son-in-law Philip Mountbatten. Philip spent a record time as royal consort and founded an award scheme under that title, raising the name to a significance it had not previously enjoyed (despite being a capital). Philip died in 2021 and his peerages were inherited by his eldest son Charles, who six months ago became King. Today Charles conferred the title for life on his youngest brother Edward.

Kendal

Style of Charles II’s nephew in 1666. He died young.

Windsor

Created by George VI for his brother, the former king Edward VIII. Edward died childless in 1972.

Some of the displays looked like they had been made many years ago and brought out unedited each time. There is a familiar style common to these kinds of displays by churches, village halls and primary schools in small settlements in rural Britain around the turn of the millennium. In particular I noticed a poster about the Crown Estate, which still referred to it paying for the civil list (as opposed to the sovereign grant).

Some of the displays looked like they had been made many years ago and brought out unedited each time. There is a familiar style common to these kinds of displays by churches, village halls and primary schools in small settlements in rural Britain around the turn of the millennium. In particular I noticed a poster about the Crown Estate, which still referred to it paying for the civil list (as opposed to the sovereign grant).