The death of Elizabeth II is a time of serious grief for her family and her many peoples. It is also a time of mild confusion for public bodies, and of course Wikipedians. Here is a run-down of some of the changes that have recently been made.

The Monarch

The man long known as Charles, Prince of Wales is now King. For many years there had been speculation that he would take the regnal name George VII in honour of his maternal grandfather and great-grandfather, but shortly after his accession it was confirmed that he would indeed go by Charles III. There was a brief period when his page was at Charles, King of the United Kingdom before being changed to Charles III. There is an ongoing debate as to whether the article title should include “of the United Kingdom”. The side in favour argues that there have been many other monarchs over the centuries called Charles III from whom the present monarch needs to be differentiated. The side against argues that Charles is king of far more than just Britain, and that if you included one realm in his title you would have to include all of them, lest you imply that one is more important than another.

The Consort

The Consort

Camilla Shand, at the time of her marriage in 2005, was not popular among much of the public still grieving Diana Spencer. So as to avoid appearing to usurp her legacy, she never styled herself “Princess of Wales”, instead going by “Duchess of Cornwall”. It was also suggested back then that, upon her husband’s accession, she would be styled “Princess Consort” (presumably derived from Prince Albert) rather than Queen. How true this proved to be was always a matter of public relations rather than constitutional law. By the start of this year it was clear that her reputation had recovered sufficiently to abandon that idea, and Elizabeth II in an open letter explicitly endorsed her daughter-in-law to be called Queen Consort. Currently all major media and government sources are very insistent on styling her “The Queen Consort”, rather than simply “The Queen” as other queens consort were before her. It is not yet clear if she will be described this way for the whole of Charles’s reign or if it is simply a temporary measure so as not to confuse the public while the late queen regnant is still being mourned. Again, there is dispute over whether her article title should include “of the United Kingdom”.

The Heir Apparent

The Heir Apparent

In 2011 Prince William of Wales was ennobled by his grandmother as Duke of Cambridge, Earl of Strathearn and Baron Carrickfergus in the peerage of the United Kingdom. He has not ceased to hold these titles, but they are now buried beneath several others. The dukedom of Cornwall, in the peerage of England, is governed by a 1337 Charter instructing that it belongs automatically to the eldest living legitimate son of the incumbent monarch and the heir apparent to the throne, and that if these two statuses are held by different people then the title is left vacant. This means that all dukes (save Richard of Bordeaux) are deemed to have held the original peerage, rather than it being created anew each time. The Duchy of Cornwall, a substantial land-holding corporation in the south of England, is governed by the same. The dukedom of Rothesay in the peerage of Scotland is mandated by an Act of Parliament from 1469 to follow an identical succession, as are the titles Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew, Lord of the Isles, Prince of Scotland and Great Steward of Scotland. The titles of Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester, by contrast, are not automatic. They are conferred by letters patent at the discretion of the monarch. It appears from news reports that Charles III has opted to do so almost immediately after coming to the throne, though I am still waiting to see this formally confirmed in the Gazette or the Court Circular. There was a short interlude in which the royal website and Wikipedia styled him “Duke of Cornwall and Cambridge”. I argued that it was poor form to include Cambridge while leaving out Rothesay, to which an anonymous user replied:

It would, but we don’t have a basis for that usage in Wikipedia practice. The hierarchy is very much What the Papers Say > legal/heraldic/formal/official names > anything that actually makes sense. I’m guessing there will be a followup announcement about his distinct style in Scotland and indeed in Northern Ireland, and maybe they’ll end up with something more logical and less clumsy. After workshopping every other possibility.

The Others

The Others

The accession of a new sovereign causes a reshuffle in the orders of precedence among the royal family. In the male order, Charles is naturally now on top. His sons William and Harry also move up, as do his grandsons George, Louis and Archie (their position before, as great-grandsons of the sovereign, was a little unclear). Andrew and Edward are demoted from sons to brothers, James and Peter from grandsons to nephews, and the Earl of Snowdon from nephew to cousin. The Dukes of Gloucester and Kent and Prince Michael are unaffected. On the female side Camilla achieves supremacy, followed by Catherine, then Meghan, then Charlotte, then Lilibet, then Sophie, Anne, Beatrice, Eugenie, Louise, Zara, Birgitte, Katharine, Marie-Christine, Sarah and Alexandra.

The styles and titles of Charles’s descendants are also upgraded (though those of his siblings and niblings are not diminished). William and Harry both gain a definitive article in their princely titles. George, Charlotte and Louis are now “of Wales” rather than “of Cambridge”. There has, of course, already been a famous Princess Charlotte of Wales, so until an alternative solution emerges their Wikipedia pages must be differentiated by the awkward use of years in brackets. Archie and Lilibet, as children of a younger son of the sovereign, now qualify as royals under the terms of the 1917 letters patent. They could now correctly be styled as “His Royal Highness Prince Archie of Sussex” and “Her Royal Highness Princess Lilibet of Sussex”, though no move has been made in that direction so far. The situation regarding the Earl of Wessex’s children remains ambiguous. Charles could, of course, amend or revoke the letters patent however he wishes, but there has not yet been any indication in that regard.

The dukedom of Edinburgh, earldom of Merioneth and barony Greenwich, which were conferred by George VI on his daughter’s fiancé Philip Mountbatten in 1947, and were then inherited by Charles in 2021, have now merged with the crown. Any of them can be bestowed anew on whomever His Majesty chooses. His brother Edward has long been presumed to receive them next, but no decision has been taken at this time.

Under the Regency Act 1937 Camilla (consort) and Beatrice (fourth adult in line) have become Counsellors of State.

The office of Lord Great Chamberlain of England (not the same as Lord Chamberlain of the Household) has automatically transferred from the 7th Marquess of Cholmondeley to the 7th Baron Carrington. The former therefore loses membership of the House of Lords under Section 2 of the 1999 Act while the latter gains it. What happens to the place he already held among the ninety elected hereditary peers is still to be determined.

The Courts

The Courts

The Queen’s Bench Divisions of the High Courts of England & Wales and of Northern Ireland, as well as the Courts of Queen’s Bench for the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Manitoba, New Brunswick and Saskatchewan, have all been renamed King’s Bench. The status of Queen’s Counsel in Australia, Britain, Canada and New Zealand has likewise changed to King’s Counsel, and all who hold it have had to amend their post-nominals accordingly. Only last month I created a new template for judges of the Queen’s Bench Division and had scrupulously added the specification to each of their infoboxes. Now I have had to change all of them. Still, it helps boost my edit count I suppose.

UPDATE (March 2023)

A few months late but better than never, the Palace now confirms that Archie & Lilibet have princely titles, as well as that Edward has become a duke.

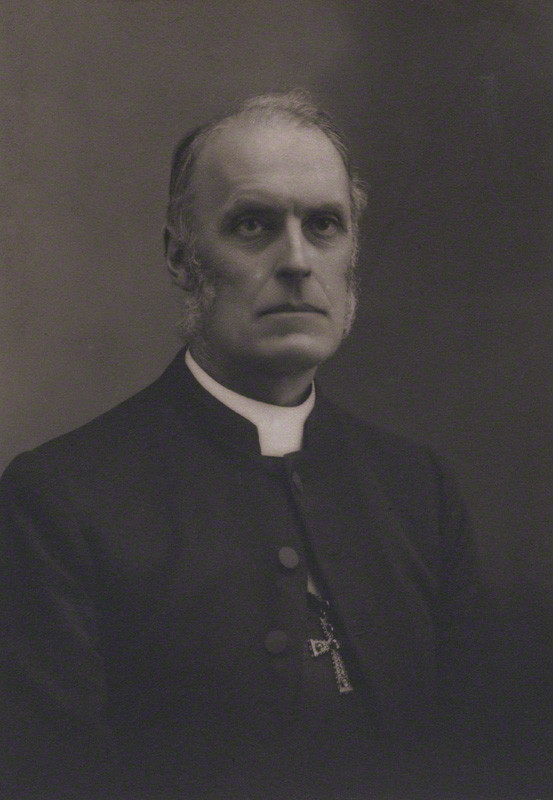

Three years ago I had a stab at designing a coat of arms for the Reverend Wilbert Vere Awdry, believing that he never had one officially granted or descended to him. Now, however, I discover that he most likely did.

Three years ago I had a stab at designing a coat of arms for the Reverend Wilbert Vere Awdry, believing that he never had one officially granted or descended to him. Now, however, I discover that he most likely did.

Before the release of the

Before the release of the

The Consort

The Consort The Heir Apparent

The Heir Apparent The Others

The Others